Few playwrights–fewer than I can count on two hands–can match William Shakepeare’s popularity over time. Four hundred years after his death, he is universally revered, frequently performed and freely adapted. The compact exhibit Shakespeare’s Characters: Playing the Part, on display now through January 8 in Gallery 6 of the Toledo Museum of Art, celebrates the playwright’s continuing relevance to literature, visual art and theater.

Using paintings, prints and artifacts from the museum’s collection as well as a few pieces from private collectors and from the Blade Rare Book Room of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, Mellon Fellow Christina Larson has curated a fascinating exhibit that traces the path of Shakespeare’s plays through time and taste. She explains:

“We saw this [the 400th anniversary] as a great opportunity to honor the Bard with an exhibition. The focus on Shakespeare’s characters came about after I had looked at Shakespeare-related artwork on view and in storage. This seemed like the unifying theme and one that would likely grasp the attention of the public …Overall, the exhibition is about inspiration and influence. Shakespeare’s characters were greatly influenced by mythology and medieval tales, while his plays and sonnets have influenced visual artists and musicians”

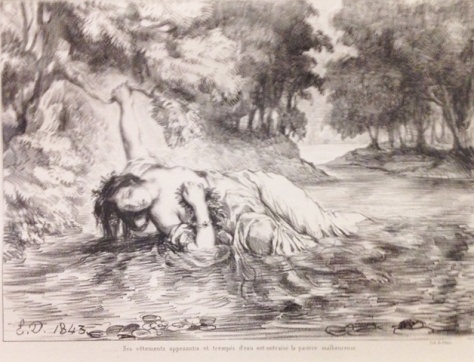

Since she was limited in her curatorial choices to works available in the Toledo area, for Playing the Part Larson has occasionally been forced to draw comparisons between artworks and plays which are not among Shakespeare’s best or most frequently produced. The never popular–and possibly never produced– Troilus and Cressida is represented, rather tangentially, by a beautiful Greek calyx krater attributed to the Rycroft Painter. But Shakespeare’s popular and frequently performed Hamlet seems to have been a great favorite as a subject among visual artists of the 18th and 19th century and is amply represented here. Ophelia in particular was a literary figure of great interest, the pure female victim being a favorite trope of the time, and is seen in this exhibit most memorably in Arthur Hughes’s large portrait of the doomed heroine. This lushly painted canvas, the curator’s favorite in the exhibit, is restrained and moody and loaded with late Victorian symbolism if you know what to look for. This is a major work by the pre-Raphaelite artist and one of the most famous in the museum’s collection. Delacroix’s small lithograph of Ophelia, from a series of 13 he created, treats the same subject in a more theatrical vein, and an etching by Eduard Manet of the actor Philibert Rauviere as Hamlet shows that interest in Shakespeare’s plays was not limited to the English.

Because Playing the Part is a temporary exhibit, the curator was able to include work that, because of its delicacy, age or condition could not be installed in the museum’s more permanently displayed collection.

“Much of the exhibition features prints and photographs. Due to conservation concerns around lighting, this artwork cannot be on permanent view, so an exhibition is the perfect opportunity to feature the artwork for a shorter duration of time,” Larson says.

Photographs by George Platt Lynes (1907-1955), of actors in a production of A Midsummer’s Night ‘s Dream are a particularly good example of rare artworks on limited view. Lynes, a photographer of the 1930’s and 40’s, was noted for his theatrical and fashion photography as well as male nude photographs now in the collection of the Kinsey Institute. Another lovely and more contemporary example of rare book art is Ronald King’s unbound, handwritten text with drawings, of Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra (1979).

Shakespeare’s plays enjoyed renewed popularity across all classes in 18th century Britain as can be seen in the many volumes reprinting and illustrating his plays in this exhibit. For both the social elite and the newly prosperous English middle class of the time, the vogue for reprinted editions of his works illustrated their emerging patriotic and egalitarian ideals as the British Empire became a global power. The Boydell Shakespeare Folio, 5 engravings from which are represented in this exhibit, was emblematic of the veritable Shakespeare industry that developed during this period.

Of the many delights in this eclectic show, my personal favorite is Iago’s Mirror (2009) by African American artist Fred Wilson. This sinister, opaque-yet-reflective baroque mirror of Murano glass is a (literal) reflection on blackness with all its moral, spiritual and racial implications, and shows that Shakespeare’s timeless story of jealousy, villainy and death in Venice remains resonant for contemporary artists and audiences.

Playing the Part establishes without a doubt that William Shakespeare found his genius while rummaging around in the cultural closet of western civilization. The enduring relevance of Shakespeare’s art comes, not from the conceptual novelty of its premises but from the originality of its execution. He could make a threadbare story feel fresh, the unbelievable seem inevitable, the fanciful seem irresistible. His greatness still resonates with visual artists and has inspired them in turn to create works of genius.

In addition to the works on display in this exhibit, Christina Larson and the staff at the Toledo Museum of Art have assembled a packed schedule of related programming, from lectures to film to musical and theatrical performances. And there’s even a Spotify playlist of Shakespeare’s sonnets and music inspired by Shakespeare. For related museum programs go here